The first few waves of defaults are hitting … the debt refinancing disaster on the way … assessing the scope of the problem … what it means for your portfolio

It feels different than prior cycles. You’re going to see a lot of defaults.

That comes from Richard Cooper, a partner at Cleary Gottlieb, which is a top law firm specializing in corporate bankruptcies.

Cooper’s skill is helping corporations when they’re drowning in debt – something he did during the Global Financial Crisis, 2016’s oil bust, and the Covid-19 implosion.

After a brief stretch of quiet, he’s back at it thanks to corporate bankruptcies that are now snowballing at the second-fastest pace in 15 years (outdone only by the early days of the pandemic).

Stepping back, regular Digest readers know that my broad stance toward today’s market has been “trade it while the bullishness is here.” But my core anxiety hasn’t disappeared. And a huge reason for that is what Bloomberg just referenced as “a $785 billion wall of debt that’s coming due” (the wall is actually far greater than that – more of those details shortly).

The idea that we’ve seen the worst of this economic cycle and it’ll be smooth sailing from here ignores a massive storm cloud directly ahead of us.

So, yes, let’s trade today’s bullishness – but do so with an awareness of what’s on the way.

Get ready for the most defaults since the global financial crisis

Let’s begin by turning to Bloomberg to set the stage:

…Underneath [today’s apparent healthy economic conditions] there’s…a deeper, and more troubling, through-line: Debt loads that swelled during an era of unusually cheap money.

Now, that’s becoming a heavier burden as central banks ratchet up interest rates and appear set to hold them there for longer than nearly everyone on Wall Street expected…

In the US, the amount of high-yield bonds and leveraged loans — which are owed by riskier, less creditworthy businesses — more than doubled from 2008 to $3 trillion in 2021, before the Federal Reserve started its steepest rate hikes in a generation, according to S&P Global data.

We’re on the cusp of this “debt refinancing” hurricane that’s coming due over the next few years. We’re talking trillions of dollars of debt rolling over at higher rates. The first bands of rain of this hurricane are only now hitting the economy.

Back to Bloomberg for what that looks like:

[The corporate insolvencies are] starting to happen already, with more than 120 big bankruptcies in the US alone already this year.

Even so, less than 15% of the nearly $600 billion of debt trading at distressed levels globally have actually defaulted, the data show. That means companies that owe more than half-a-trillion dollars may be unable to repay it — or at least struggle to do so.

Meanwhile, earlier this week, Moody’s Investors Service upped its estimate for the global default rate for speculative-grade companies over the next year. Instead of 3.8%, Moody’s now thinks we’ll see a 5.1% default rate. And its most pessimistic forecast is 13.7%, which would exceed the default rate of the global financial crisis.

How do we tie this more clearly to the stock market and your portfolio?

Well, let’s begin by looking at the Russell 2000, which is an index comprised of 2,000 of the smallest stocks in the market.

According to the research shop Apollo, back in the 1990s, about 15% of Russell 2000 companies had negative 12-month earnings. Today that percentage clocks in at an astonishing 40%.

How have these companies survived with no earnings?

Cheap debt.

Here’s The Wall Street Journal with more details:

In 1990, Federal Reserve data show that the interest paid by nonfinancial corporate businesses as a share of their outstanding debt, a proxy for the average interest rates they were paying, came to 13.3%.

By 2021—the last year with available data—that had fallen to 3.6%, marking the lowest level since the late 1950s.

So, what do you think will happen when the 40% of the Russell 2000 companies with no earnings, surviving thanks to cheap debt, soon find themselves having to service expensive debt?

And don’t write this off as a small-cap problem. Even if you’re invested in massive companies, the interest rate jolt that’s coming could materially impact earnings and/or slow business growth – which would hit stock prices.

For example, take the biopharma giant Gilead, which funds part of its corporate growth with bond issuances.

Gilead’s annual report shows that the interest it’s been paying on at least one of its notes that matures this year is only 0.75%. Meanwhile, what’s the prevailing interest rate it will have to offer to raise money in today’s corporate environment?

Moody’s tells us it has averaged 5.6% so far this year. So, about 650% higher.

Back to the WSJ for the consequence on your portfolio:

…Companies could have some difficult choices to make in the years ahead.

Some will likely decide to reduce their debt loads, choosing either to curtail investment and expansion efforts, or to finance those efforts by other means, such as issuing equity.

Others will refinance their maturing debt at higher rates, with higher borrowing costs weighing on earnings as a result.

Neither of those possibilities seem all that pleasing to stock investors.

Don’t look for a guillotine chop, it’ll be more of a slow boil

Because corporate debt matures on different timeframes, there won’t be a single doomsday calendar event when the pain arrives. Our earlier analogy of a hurricane is more accurate, with the impact ratcheting up over time.

Back to the WSJ with the specifics of these waves of economic pain:

S&P Global Ratings analysts recently calculated there is a manageable-seeming $504 billion in U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt maturing this year.

That will be followed by $710 billion in 2024, $862 billion in 2025 and $880 billion in 2026.

Since companies usually refinance their debt 12 to 18 months before it matures, the effect of that overhang of maturing debt could come sooner than many investors realize.

Even if corporations avoid a huge wave of defaults, that doesn’t mean a small number won’t have damaging economic ripple effects. And right now, investors are ignoring it.

Here’s Bloomberg:

A relatively modest uptick in defaults would add another challenge to the economy.

The more defaults rise, the more investors and banks may pull back on lending, in turn pushing more companies into distress as financing options disappear.

The resulting bankruptcies would also pressure the labor market as employees are let go, with a corresponding drag on consumer spending.

What this default risk means for you today

In the short-term, it means very little.

We’re in a bull market. As we’ve been saying for months now, let’s trade it while it’s here (though we’ve suggested we’re due for a pullback which the Nasdaq might be beginning as I write on Thursday).

But there are very real economic problems headed our way. The only way to avoid them is if the Fed swings to rate-cuts – and not by just a quarter-point or two. We would need a full-blown rate-cut bonanza over the next couple years to avoid the refinancing pain that’s in the pipeline over the next 18-to-24 months.

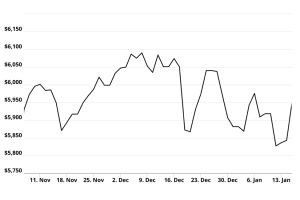

As we stand today, such a bonanza appears highly unlikely unless the economy is melting down. That’s because the Fed doesn’t like to “taper” interest rates. History shows that it holds them high until it breaks the economy, forcing a cliff-edge interest rate drop. See for yourself…

Below we look at the Federal Funds Effective Rate since the mid-90s. Do you see any smooth, downward-stairstep interest rate declines?

No, you see panicked interest rate freefalls that correspond to the Dot Com crash, the Global Financial Crisis, and the Covid-19 pandemic.

“But, Jeff, what about that stretch of elevated interest rates in the 90s before the Dot Com crash? That occurred during years of big stock market gains.”

True – and that’s why our current stance is to continue trading today’s bullishness while it’s here. But it doesn’t change what history shows was the result of those lingering, high interest rates.

So, what’s the takeaway?

As just noted, continue trading today’s bullishness.

But examine your portfolio to assess your exposure to interest rate risk. Which companies have debt rolling over in the next couple years? How much debt?

Pay attention to construction, manufacturing, REITs, telecom, some healthcare, and yes – even some beloved (yet unprofitable) tech companies. Historically, businesses in these sectors require loads of debt to operate, making them vulnerable to this refinancing risk.

So, ride these stocks higher while “higher” is the prevailing market direction. But mind your stop-losses and your position sizes if/when market direction changes.

Bottom line: The slow boil is beginning. Don’t be the frog in the pot.

Have a good evening,

Jeff Remsburg