The failure to conduct second-level thinking … who wins in the autonomous vehicle wars? … what a second-level analysis suggest for price controls … gold sets a new all-time high

But then what might happen?

That’s the question that most people (and investors) aren’t great at asking – much less answering correctly.

We’re decent at looking one step ahead to that first fork-in-the-road decision and its potential outcomes. But beyond that, most people stop evaluating.

Too often, this lack of “second-level thinking” leads to an array of suboptimal outcomes. In the investment world, the consequence is usually underperformance.

In his book, The Most Important Thing, the co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Howard Marks writes:

First-level thinking is simplistic and superficial, and just about everyone can do it (a bad sign for anything involving an attempt at superiority).

All the first-level thinker needs is an opinion about the future, as in “The outlook for the company is favorable, meaning the stock will go up.” Second-level thinking is deep, complex and convoluted.

Let’s begin today’s Digest by looking at an example of first- and second-level thinking through a lens of AI investing. We’ll do this with the help of our macro expert, Eric Fry.

As we noted in last Friday’s Digest, Eric is holding a live event this Thursday at 1 PM ET called the Road to AGI Summit. It’s a summary presentation of his months of research into the investment implications of AGI, or “Artificial General Intelligence.”

The ability to ask, “but then what might happen?” will be critical to investment success in the world of AGI.

What’s the best way to invest in the auto industry in the coming age of AGI and autonomous vehicles?

Let’s begin with the first-level way of analyzing this market. Here’s Eric:

At first glance, observers might believe that the Road to AGI involves winners, automakers like General Motors Co. (GM), and losers, rideshare firms like Uber Technology Inc. (UBER).

However, a closer look at the industry reveals the opposite might be true once autonomous vehicles (AVs) truly emerge. Rideshare firms could emerge as winners, while automakers become the losers.

Why? After all, in the coming era of mind-blowing technology, aren’t we all going to want these next-gen autonomous-driving cars of the future?

Well, with first-level thinking, yes, of course we will. And this means there’s likely to be huge demand for the manufactures of autonomous vehicles.

But what does second-level analysis reveal?

Eric points out a critical overlooked detail…

Cars are parked 95% of the time. So, there’s enormous utility that’s not being used. Up to now, this utility was locked because, without a driver, cars were little more than very expensive paperweights.

But with AI, we’re entering a world where cars can drive themselves. This frees them up to service an entire family, or household, or group of friends. Cars are no longer tethered to their user.

So, instead of a family where mom and dad have their own cars, and two teens share a third car, there’s now the potential for one car to ferry about each family member effectively (assuming compatible scheduling). Or better yet – how about avoiding the cost of buying cars entirely (and scheduling complications), and just paying for their occasional use?

Through this lens, notice that the emergence of autonomous vehicles shifts the value-add away from the vehicle itself, and toward the vehicle’s trip.

Back to Eric:

The rideshare firm Uber stands to benefit from AGI because it can quickly become a marketplace for these services.

Why buy a Tesla Robotaxi when Uber can send you the nearest car for the cheapest price?

So, if rideshare companies like Uber play their cards right, they would be the ones that benefit most on the Road to AGI, rather than the automakers that finally perfect autonomous driving.

Again, Eric will be discussing this type of second-level thinking this Thursday, August 22, at 1 p.m. ET at his The Road to AGI Summit. To reserve your seat, click here. This type of deeper analysis will be critical for investors in the coming age of AGI.

Meanwhile, let’s look at the potential risks of a failure to consider second-level thinking in our economy

Over the weekend, Vice President Harris presented her first major policy initiative if she’s elected president – a proposed ban on “price gouging.”

From Harris:

We all know that prices went up during the pandemic when the supply chains shut down and failed. But our supply chains have now improved, and prices are still too high.

The Harris campaign added:

Vice President Harris knows that rising food prices remain a top concern for American families. Many big grocery chains that have seen production costs level off have nevertheless kept prices high and have seen their highest profits in two decades. While some food companies have passed along these savings, others still have not.

The Harris campaign went on to say that it will set “clear rules of the road to make clear that big corporations can’t unfairly exploit consumers to run up excessive corporate profits on food and groceries.”

Harris has made similar statements about the rental market, pledging to “take on corporate landlords and cap unfair rent increases.”

Now, politics isn’t our focus here in the Digest. But the economic impact of various policies can be directly in our wheelhouse due to the impact on corporate earnings, and by extension, stock prices. So, please understand, we’re evaluating a policy, not a candidate.

That said, how does this proposed policy of price controls look through a first- and second-level thinking framework?

Bad. Very bad.

The failure of first-level thinking on price controls

In the early 2000s, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez implemented strict price controls on a wide range of food staples like flour, milk, and cooking oil.

The goal of this first-level thinking appeared admirable – make essential goods more affordable for the poor in the face of rising inflation.

What the Venezuelan government failed to ask is “but then what might happen?”

So, take a moment and mull it for yourself…

From a producer/retailer perspective, what might happen when there’s a limit to what a manufacturer can charge for a good, yet its cost structure remains the same?

Well, logic suggests that the producer/retailer will either receive lower profits or no profits at all. Either way, they’re de-incentivized to produce the good.

In Venezuela’s case, the result was “no profits.” As a result, many producers/manufacturers stopped producing or importing the goods. This led to severe shortages where shelves in stores were empty, and huge lines became common as people searched for scarce items.

Meanwhile, insufficient supply led to black markets where the same goods transacted at horribly inflated prices. Better-off Venezuelans were able to afford the goods, but the poor – whom the price controls were intended to help – couldn’t pay the cost.

Venezuelan farmers found it increasingly difficult to cover their costs profitably. So, they cut domestic production, making the country more reliant on imports that were often inadequate. The increased scarcity added more upward pressure on inflation.

We could go on (mass social unrest), but you get the idea. What appeared to be an admirable first-level decision backfired horribly due to a lack of second-level analysis.

As to Harris and price gouging, what’s the definition of “gouging”? The term implies there’s some level of profit margin that would not be considered gouging. What is it? Who sets it? What’s the specific economic rationale?

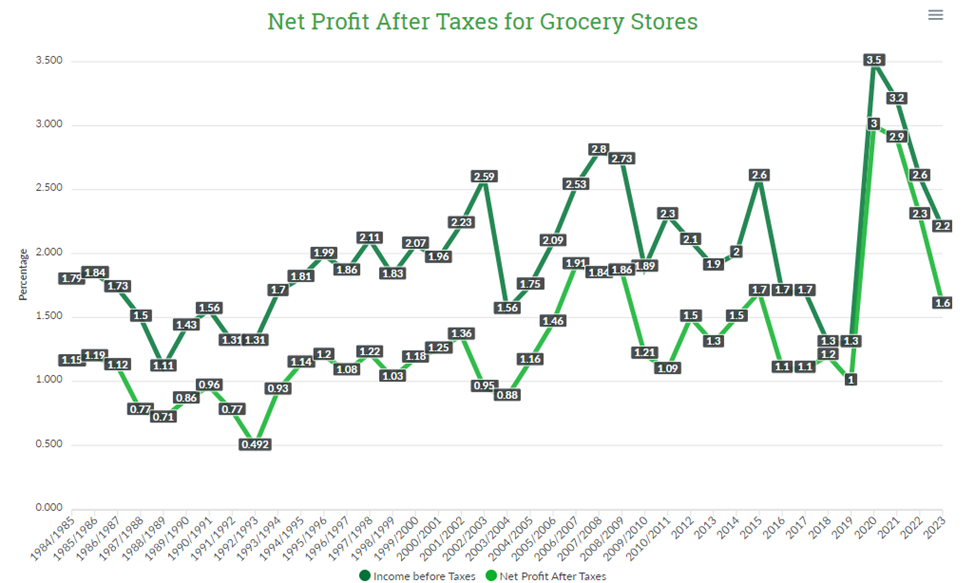

Keep in mind, margins in the big box grocery sector are razor thin – typically just 1% – 3%.

Below is a chart spanning from 1985 through last year that shows grocery stores’ net profit after taxes. You’ll see this net profit temporarily spiked to 3% in 2020, but as of last year, it fell back to 1.6%, which is roughly in-line with levels dating back to 2004.

Do you see consistent price gouging?

The same problems play out with rent-control policies. In short, if you’re not lucky enough to snag one of those rent controlled units, a market in which the natural supply/demand equilibrium has been distorted by government intervention means higher prices.

Whether Harris wins the White House or not, let’s hope this policy is abandoned. History, logic, and second-level thinking all suggest it will eventually hurt the people it’s intended to help.

Finally, be aware of second-level certainty from our own financial “experts”

Because “XYZ” hasn’t happened this time around (so far), it’s not going to happen looking forward.

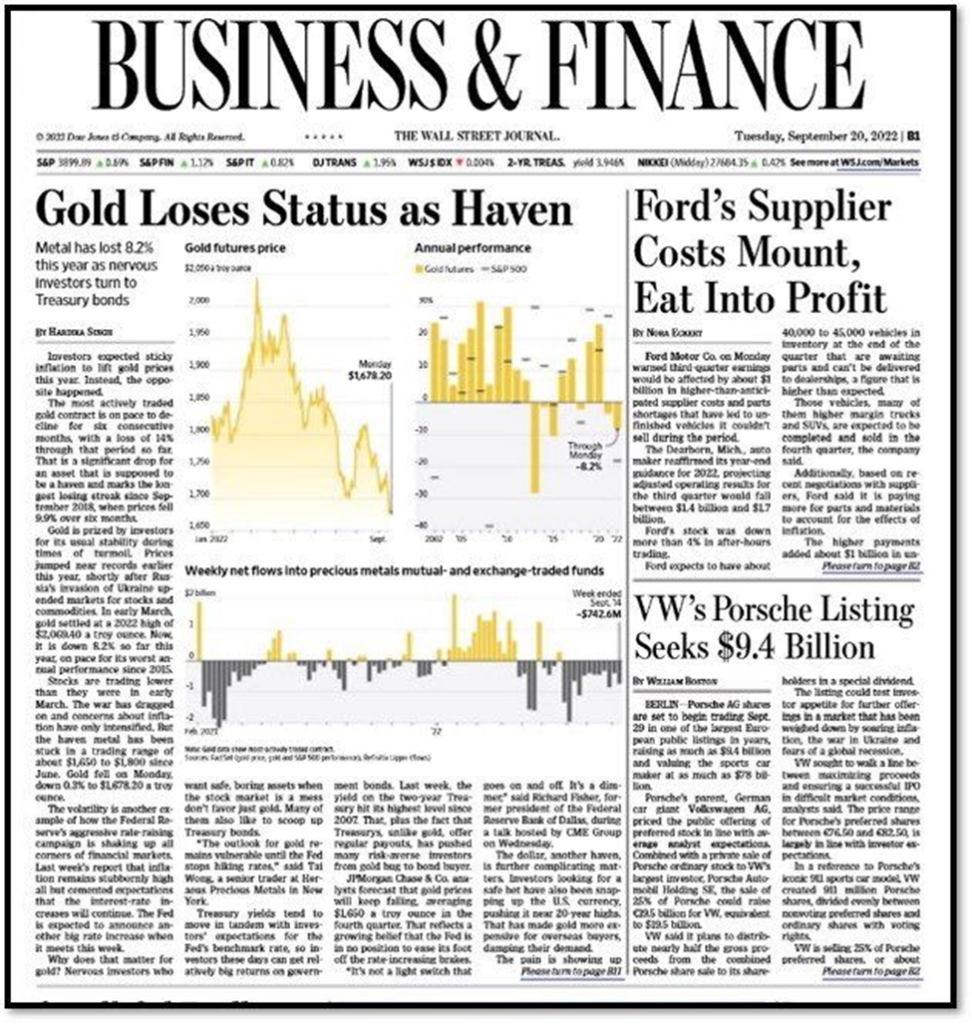

That’s the conclusion of poorly considered first-level analysis such as what we read below from The Wall Street Journal back in 2022.

If you’re having trouble seeing the main headline, it reads “Gold Loses Status as Haven.”

The article went on to highlight gold’s failure to soar in a high inflation environment. It quoted various “experts” who made bearish predictions for the yellow metal.

This type of first-level analysis implied that just because gold hadn’t raced higher up to that point, no such price gains would come.

Circling back to Eric, here’s what he wrote about gold at the same time:

The yellow metal is barely registering a pulse at the moment. Most of the wax figures inside Madame Tussauds museum seem more vibrant and lifelike.

But that’s simply how gold behaves from time to time. It “does nothing” for such extended periods of time that investors begin to doubt it could fog a mirror.

Gradually, they turn their back on the comatose metal and leave it for dead. But that’s usually about the time it comes to life.

So, how did this play out?

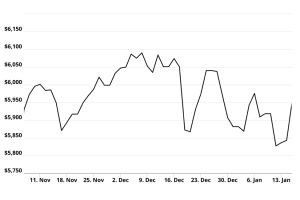

Well, since the WSJ‘s article, gold has exploded 52%, beating the S&P’s 43% gain. And earlier today, it set a new all-time high of $2,524.88 per ounce, surpassing a previous record hit on Friday.

It turns out just because gold hadn’t enjoyed a price run-up as of 2022, the conclusion that no such run-up would happen was a classic first-level error in analysis.

If anything, the slumbering price was fuel for the 50%+ surge that would come as various gold short-sellers had to liquidate their bearish positions once the precious metal finally caught a bid.

Congrats to Eric, as well as to any second-level thinkers who bought gold based on his analysis two years ago.

Bottom line: The next time we’re faced with an important decision – investment-related or not – we’d be wise to pause and ask ourselves, “but then what might happen?”

Have a good evening,

Jeff Remsburg