All the details of the first rate cut since 2020 … what Fed members predict for additional rate cuts … what does this mean for the market?

Welcome to the first rate-cutting cycle since the Covid Pandemic!

This afternoon, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 50-basis points, marking the first interest-rate cut since 2020.

It was also the first time there was dissent from a Fed Governor since 2005, as Michelle Bowman preferred a 25-basis-point cut.

We predicted this 50-basis-point cut in yesterday’s Digest, suggesting that the decision would be paired with plenty of hedging language from Chairman Jerome Powell in his press conference, referencing the strength of our economy. That’s exactly what we got.

In Powell’s official remarks, he stated:

Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace.

GDP rose at an annual rate of 2.2 percent in the first half of the year, and available data point to a roughly similar pace of growth this quarter.

Growth of consumer spending has remained resilient, and investment in equipment and intangibles has picked up from its anemic pace last year.

After going on to describe the economy as being “in a good place” in his live Q&A, he said:

We are committed to maintaining our economy’s strength. This decision reflects our growing confidence that with an appropriate recalibration of our policy stance, strength in the labor market can be maintained.

Powell downplayed the idea that the 50-basis-point cut suggested the Fed was already behind. He also seemed to jump on every opportunity to characterize the economy and labor market as being strong.

Perhaps his most emphatic comment on the topic came at the end of his press conference when he was asked about a recession.

From Powell:

I don’t see anything in the economy right now that suggests that the likelihood of a recession – sorry, a downturn – is elevated. Okay? I don’t see that.

However, earlier in his press conference, there was a related, awkward exchange.

When asked why the unemployment rate would peak at 4.4% next year as is the Fed’s estimate when history shows that unemployment rates rarely stop at such low levels after they rise quickly as our has done in recent months, Powell’s waffling non-answer caught my ear.

From Powell:

Again, the labor market actually is in solid condition. And our intention with our policy move today is to keep it there.

You could say that about the whole economy. The U.S. economy is in good shape. It’s growing at a solid pace. Inflation is coming down. The labor market is in a strong place. We want to keep it there. That’s what we’re doing.

Powell then abruptly stopped speaking. The camera panned to the reporter, who looked around awkwardly.

I found myself thinking, “Um, okay, but what about a reply to the actual question? Why will unemployment just miraculously stop at 4.4% next year when it usually doesn’t?”

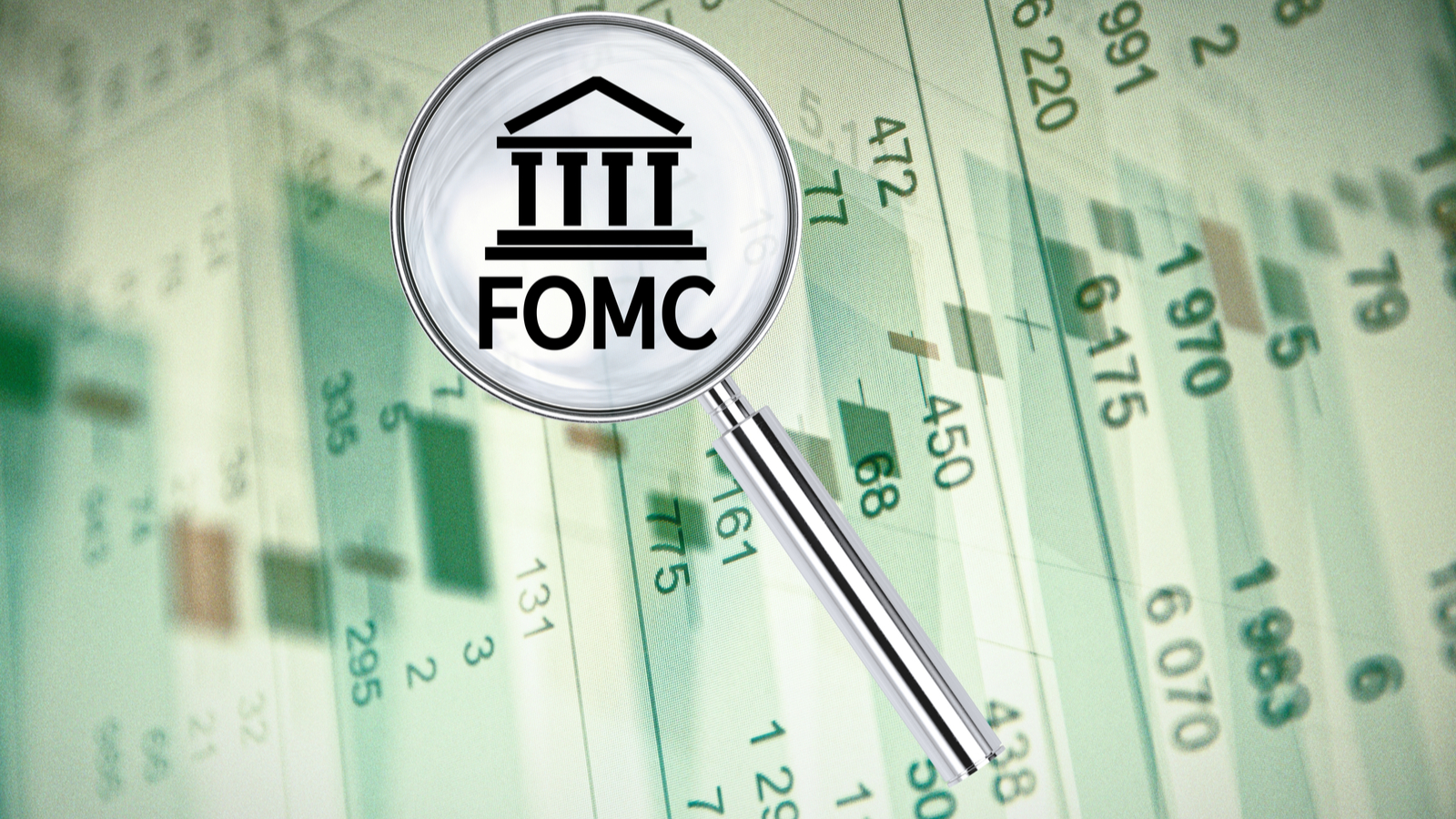

Meanwhile, what did the Fed’s updated Dot Plot reveal about where rates go from here?

To make sure we’re all on the same page, the Dot Plot is a graphical representation reflecting each committee member’s anonymous projection of where they believe rates will be at specific dates in the future. The Fed members update the Dot Plot once every three months.

In both the December and March FOMC meetings, the Dot Plot showed a median forecast of three quarter-point rate cuts in 2024.

The June Dot Plot pared that back to just one rate this year. Also, remember that in June, four Fed members predicted no cuts at all in 2024.

How much can change in just three months!

The latest consensus projection now calls for two more 25-basis-point-cuts this year, followed by four more quarter-point cuts next year, then two more quarter-point cuts in 2026.

And here’s more from Yahoo! Finance with additional details from the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP):

The SEP indicated the Federal Reserve sees core inflation peaking at 2.6% this year — lower than June’s projection of 2.8% — before cooling to 2.2% in 2025 and 2.0% in 2026…

The Fed slightly lowered its previous forecast for US economic growth, with the economy expected to grow at an annualized pace of 2.0% this year and remain at that level through 2025 and 2026.

As to the market’s reaction, stocks leapt higher just after the announcement of the 50-basis point cut but then they gave up their gains.

As we predicted yesterday, the market took profits on the news, though it was hardly a major selloff. Though all three major indexes closed lower, the losses were mild.

Tomorrow and Friday will be the more telling days after traders and investors have time to digest the news.

So, beyond the immediate short-term, where will the market go from here?

Yesterday, our hypergrowth expert and editor of Innovation Investor, Luke Lango, crunched the numbers:

Since 1987, the central bank has embarked on seven different rate-cutting cycles, according to Bloomberg. In five of those instances, the S&P 500 rallied three, six, and 12 months after the first rate cut, with nearly 8% average returns the following year.

Empirically speaking, rate cuts do tend to spark stock market rallies.

But ‘good’ rate cuts usually spark massive stock market rallies. And that’s exactly what we’re approaching right now.

Luke explains that when the Fed is proactively cutting interest rates while the economy is still healthy (positive GDP, low joblessness, etc.), rate cuts are “good.” Those lower rates goose a sluggish economy and invigorate the stock market.

Alternatively, rate cuts are “bad” when the Fed is reactively cutting them in response to an already-troubled economy (weak GDP, high joblessness, etc.). Too often, those cuts fail to resuscitate the economy, which continues to weaken. Stocks suffer as a result.

Back to Luke for where we are today:

Right now, the economy is currently growing at a 3% clip. Continuing jobless claims are running below 2 million. This current economic setup suggests we are going into a ‘good’ rate-cutting cycle.

And in recent ‘good’ cycles, stocks soared in the 12 months after the first cut…

We think this rally could be particularly powerful.

That’s because the rate-cutting cycle we are entering right now draws strong parallels to that of 1998/99, wherein tech stocks absolutely surged higher.

So far, so good.

But to continue refining our expectations, let’s analyze today’s valuation relative to that of prior rate-cutting cycles

Given the broadly healthy economic conditions Luke highlighted, many investors have jumped to Luke’s conclusion – we’re in for “good” rate cuts, which means big-time market gains once they’ve begun.

To benefit, these investors have front-run anticipated rate cuts all year long. This has pushed the S&P up 18% so far in 2024.

Now, as you’d expect, this heavy buying pressure has driven the S&P 500’s valuation materially higher.

How much higher? And how does that compare with valuations at the beginning of prior rate-cutting cycles?

To contextualize where we are today, let’s begin with prior valuations.

The highest S&P 500 valuations at the beginning of rate-cutting cycles over the last 40 years came in 2001, 1998, and 2019:

2001: Price-to-earnings ratio of 25; price-to-sales ratio of 2.0.

1998: Price-to-earnings ratio of 24; price-to-sales ratio of 1.6.

2019: Price-to-earnings ratio of 22; price-to-sales ratio of 2.3.

To make it easy, here’s their average…

Price-to-earnings ratio of 23.6; price-to-sales ratio of 2.0.

And where are we today?

2024: Price-to-earnings ratio of 29.5; price-to-sales ratio of 3.0.

In other words, this is the most richly valued starting point for a rate-cutting cycle in modern history.

Specifically, today’s price-to-earnings ratio is 25% more expensive than the average of the prior three most expensive starting rate-cut valuations, and 50% more expensive on a price-to-sales basis.

This doesn’t mean stocks can’t or won’t soar from here, but it does suggest we should recognize the implications for longer-term returns

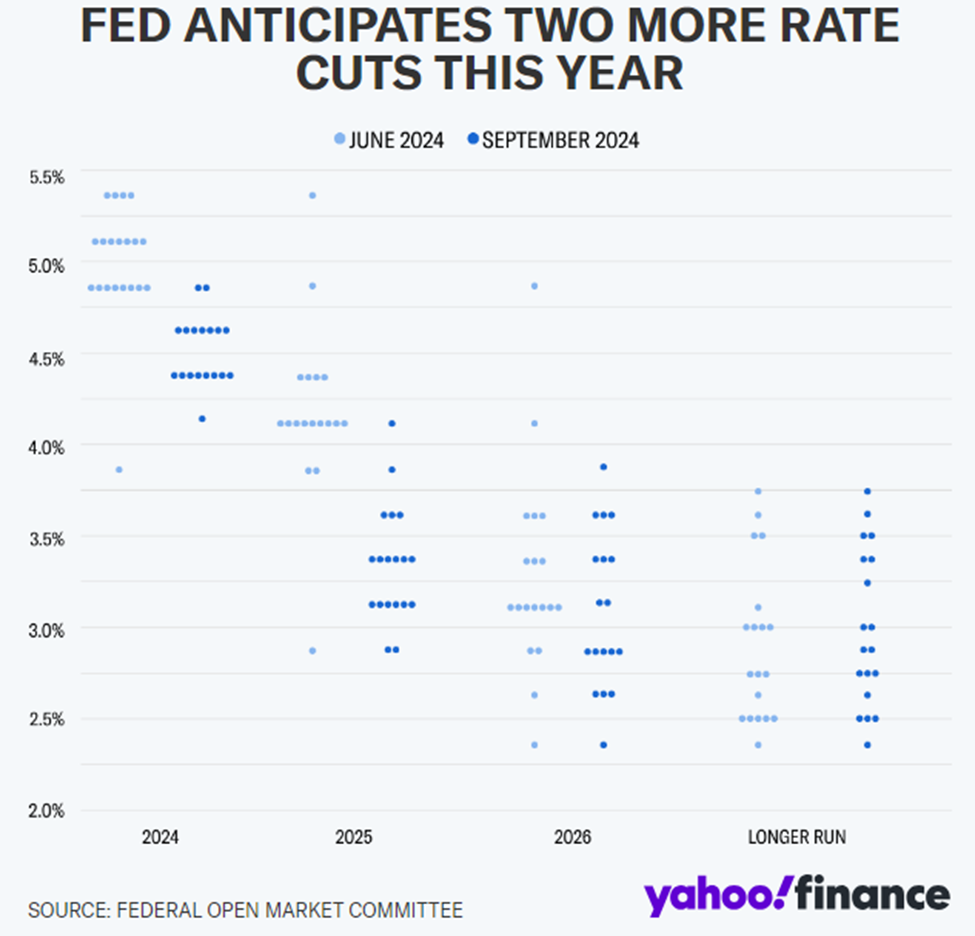

One of the ironclad rules of investing is that your initial starting valuation matters – a lot.

All things equal, the more you pay for an investment today, the lower your returns will be tomorrow. This is inarguable – it’s just basic math.

Of course, this plays out more over longer time horizons. In the short-term, stock returns can go anywhere.

For example, investor enthusiasm could easily push an overvalued market into nosebleed valuation territory over a year or two. But over, say, five to 10 years, such overblown bullish sentiment often wears off as investors wake up to valuation.

Bottom line: In the long-term, starting valuation is critically important, and largely predictive of returns.

To illustrate, below are data from LPL Financial. We’re looking at what subsequent 10-year returns have been for the S&P based on starting price-to-earnings valuations.

With today’s starting valuation of 29.5, LPL’s study suggests our 10-year return will be flat or negative.

Here’s LPL’s take:

That forecast may end up being overly pessimistic given the potential for a further structural shift higher in valuations as in prior decades, but it does suggest that another decade of double-digit annualized returns, which investors have enjoyed over the past 10 years, is unlikely.

So, how do we balance Luke’s bullishness with these less-bullish starting valuations?

Simple – you distinguish between “longer-term investing” and “shorter-term trading.”

From a longer-term investing perspective, today’s market isn’t screaming “you must buy now!” due to valuation headwinds.

Now, I’ll quickly add the disclaimer regular Digest readers will recognize: The market is not one big monolith that rises and falls in unison. It’s made up of thousands of stocks that perform differently based on their unique earnings and business environment.

And to be clear, I’m not advising you to sell your long-term, core positions. But I am saying you should be cautious and intentional about how much new capital to add to those positions at today’s lofty valuation.

On the other hand, our takeaway from a “shorter-term trading” perspective is different. The data surrounding rate cuts is fundamentally bullish. We want to take advantage of that, and we do so through wise trading.

This means we focus on investments that are showing obvious, bullish price momentum, while protecting our capital with various risk mitigation tools if that momentum turns. This approach enables us to benefit from a surging market for however long it’s here.

On this topic of “tools,” I want to put something on your radar…

Next Tuesday, our macro investor Eric Fry is sitting down with the self-described “worst investor in the world”

While that description likely raises an eyebrow, it’s relevant for our discussion of valuations and trading…

You see, this “bad” investor decided to do something about his bad investment results. He set out to create a series of tools that would help him better time his entries (before a market spike) and his exits (prior to the eventual crash).

When the project was completed, Eric took these tools and applied them to his own multi-decade track record of recommendations. He found that they would have substantially improved his (already impressive) results.

This provides us a critical reminder about investing: You don’t always need a better stock – better management of the stocks you own can do wonders.

We’ll bring you more details about these tools over the coming days, but to reserve your seat for next Tuesday, click here.

Wrapping up, a study of rate cuts suggests we’re in for solid gains in the months ahead. But a study of starting valuations suggests we’re in for a flat market in the decade ahead.

If you’re interested in how to balance this tension, benefiting from the first while sidestepping the second, join Eric and his guest on Tuesday.

In the meantime, welcome to rate cuts!

Have a good evening,

Jeff Remsburg