Shares of AMC Entertainment (NYSE:AMC) rose as much as 67% on Friday after Delaware courts denied a settlement for a planned merger of AMC’s Preferred Stock (NYSE:APE) with its common issue.

At first glance, this seems like excellent news to common AMC shareholders. A merger between the two share classes would have torpedoed AMC’s stock by increasing the total share count from 519 million to roughly 1.5 billion. It’s a zero-sum game between common shareholders and preferred stockholders.

But a failure of AMC’s management to equalize the two stocks is devastating news for the theater chain’s long-term health. With $98 million worth of bonds expiring in 2025 and another $1.5 billion due in 2026, AMC is running out of time to find the cash and refinance.

AMC Entertainment: An Old Profit Problem

AMC’s funding issues are nothing new. In the mid-2010s, the industry went through a spate of debt-fueled consolidation and expensive theater upgrades. AMC itself would spend over $400 million yearly on theaters to keep up with rivals. By 2020, AMC’s total debt had risen to $5.8 billion, while Regal Cinemas parent Cineworld Group (OTCMKTS:CNNWQ) was saddled with $8.0 billion.

Someone has to pay for those reclining seats!

In theory, the mergers and reinvestments should have turned the low-profit industry into a more profitable one. Consolidated industries tend to earn higher profits, and better theaters can charge customers more for tickets. Surly, owning every movie theater in town would mean better financial returns.

But it turns out that CEO Adam Aron missed two things.

- Covid-19 Lockdowns. The 2020 pandemic came at the worst possible time for the company’s debt repayment plan. Rather than reduce the $5.8 billion debt pile, the firm was forced to issue another $1.2 billion in bonds to stay afloat.

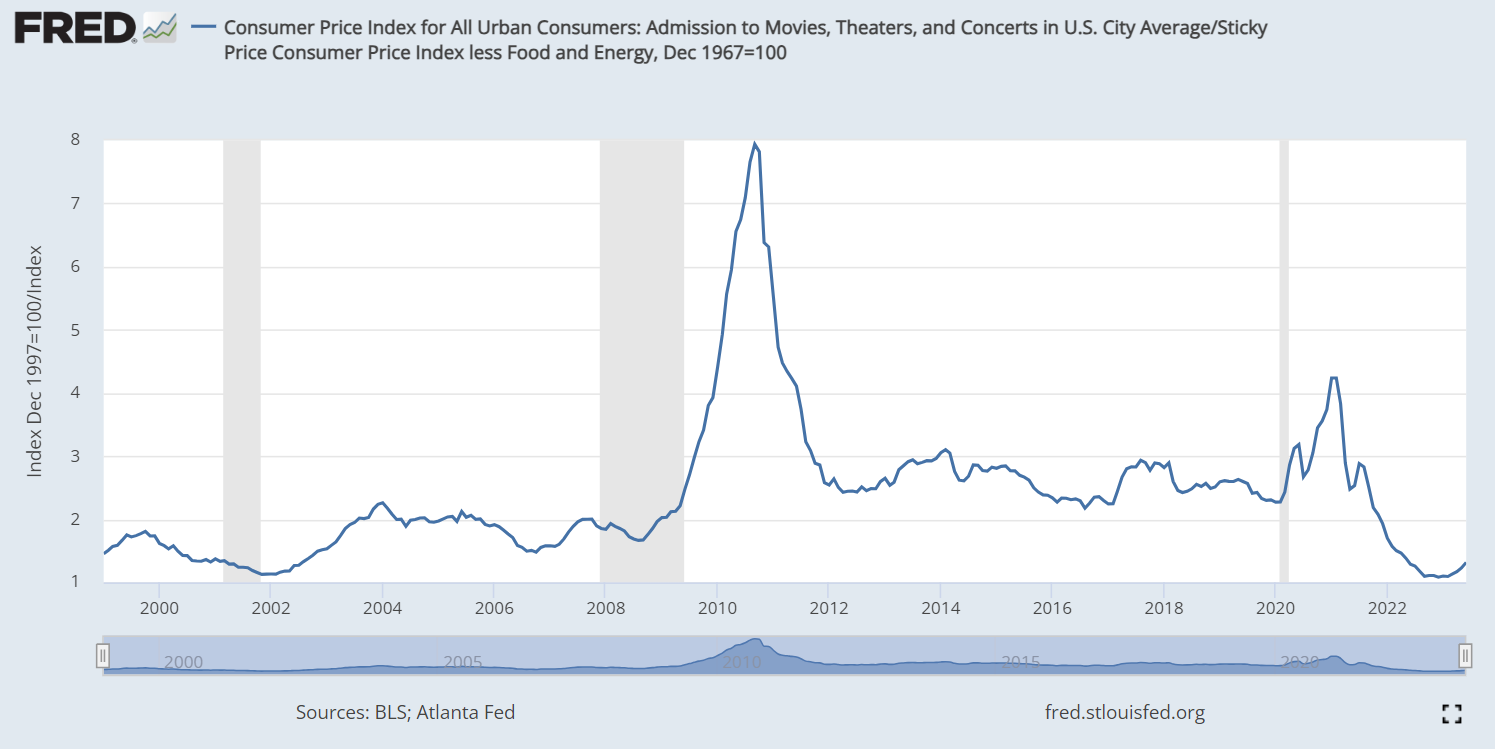

- Industry Demand. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the price of admission to movies, theaters and concerts has fallen by roughly half from pre-pandemic levels. AMC’s ticket prices themselves have failed to keep up with inflation, rising from $9.43 in 2014 to just $10.95 today.

The consumer price index for movies, theaters and concerts remain well below pre-pandemic periods

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

That means AMC Entertainment is still losing money despite management’s best efforts to consolidate the theater industry. Analysts expect the Kansas-based firm to generate $493 million in losses on $4.5 billion of revenues this year. The company must spend $450 million per year on interest payments alone.

When Good News Is Bad News

The reason, of course, is that moviegoers are not returning to theaters. Worldwide box office revenues only hit $7.4 billion in 2023, down from $11.9 billion in 2018. A slow start to 2023 (Barbie and Oppenheimer notwithstanding) means this year’s take might barely hit $10 billion.

Instead, viewership has moved to streaming services and TV. In 2015, there were 370 scripted shows on the air. Last year, there were 599.

Theatergoers have also been tightening their belts. This week, AMC quietly announced it would drop its controversial variable pricing plan that charged viewers higher amounts for better seats.

That means AMC’s debts will prove impossible to pay off.

So far, AMC’s management has plugged the funding gap by issuing new shares and skimping on theater renovations. In 2020, the firm raised $265 million through share issuances and saved roughly $250 million by reinvesting less into their business. In 2021, the combined figure had risen to around $2.1 billion.

That’s clearly unsustainable. The company is now left with $496 million in cash-on-hand and covenants that require at least $100 million of liquidity. That means AMC’s current $185 million quarterly cash burn will deplete the firm’s liquidity as early as 2024 unless the firm issues more stock.

Upcoming bond maturities over the next several years will also strain AMC’s funding. Without clear guidance from Delaware courts, borrowers will have less incentive to allow AMC to roll these bonds forward at low rates.

How to Fix a Broken Business

In truth, the AMC/APE convergence might have been enough to save AMC from bankruptcy. The theater is profitable on a pre-interest basis, so converting all debt to equity would theoretically allow the firm to continue as a going concern (even if not a particularly profitable one).

But “surviving” isn’t the same as “thriving.” For AMC to earn its cost of capital, it will need to generate at least $800 million of annual profits, assuming its invested capital base of $9.3 billion remains unchanged. For it to truly succeed, that figure will have to be in the $1 billion-plus range.

Doing so will require some imagination. $800 million of profits translates to roughly $1.3 billion of additional revenue, since movie studios take a portion of ticket sales. And raising prices by a third will send demand plummeting, as evidenced by AMC’s experiment with premium seat pricing.

Some believe this is a management issue. Adam Aron became CEO in 2015 and oversaw AMC’s spending spree. (If only they could hire Ryan Cohen to fix this mess!) Others might view it as a share price issue. (If only we bought in all at once, the stock will go to the moon!)

In reality, the problem is a demand one. Consumers have grown used to paying less than $10 monthly for an all-you-can-watch buffet of movies and TV shows. Many firms like Walmart (NYSE:WMT) are even experimenting with free streaming services for members.

That leaves firms like AMC in purgatory. The firm isn’t quite broken enough to go out of business immediately, nor is it healthy enough to succeed. And much like purgatory, there’s little to do but wait around and hope that a “fixer” eventually comes to the rescue.

As of this writing, Tom Yeung did not hold (either directly or indirectly) any positions in the securities mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer, subject to the InvestorPlace.com Publishing Guidelines.