In mid-2014, shares of mortgage insurer Genworth Financial (NYSE:GNW) began to wobble. Home prices in Australia and Canada were surging, and investors believed it was only a matter of time before the bubble burst. Genworth was the most obvious candidate to lead the meltdown.

But the bubble didn’t pop. Not then, anyway.

Median Australian home prices would rise another 12.1% the following year and then another 7.6% after that. By 2017, the median home price hit a staggering $1.03 million. A similar situation unfolded in Canada, with property values trending up for another seven years until 2022. Like unwanted relatives at a Thanksgiving party, high home prices stick around longer than people think.

A similar situation is unfolding in America today. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the average home price now sits at $416,100, 25% higher than in 2019. Prices have risen as much as 66% in high-growth areas like Florida and Texas. This year, we will likely see another 5%-10% increase in real estate prices nationwide.

Eventually, home prices will cool down. No tree can ever grow into the sky, and no real estate market should ever grow larger than its underlying economy. But history tells us that U.S. real estate is not due for a crash soon.

Despite rising rates, increasing unaffordability, and slowing economic growth, home prices will likely keep surging anyway. Renters and potential homebuyers beware: The pain will only worsen before things get better.

Why Home Prices Will Keep Surging: Shifting Affordability

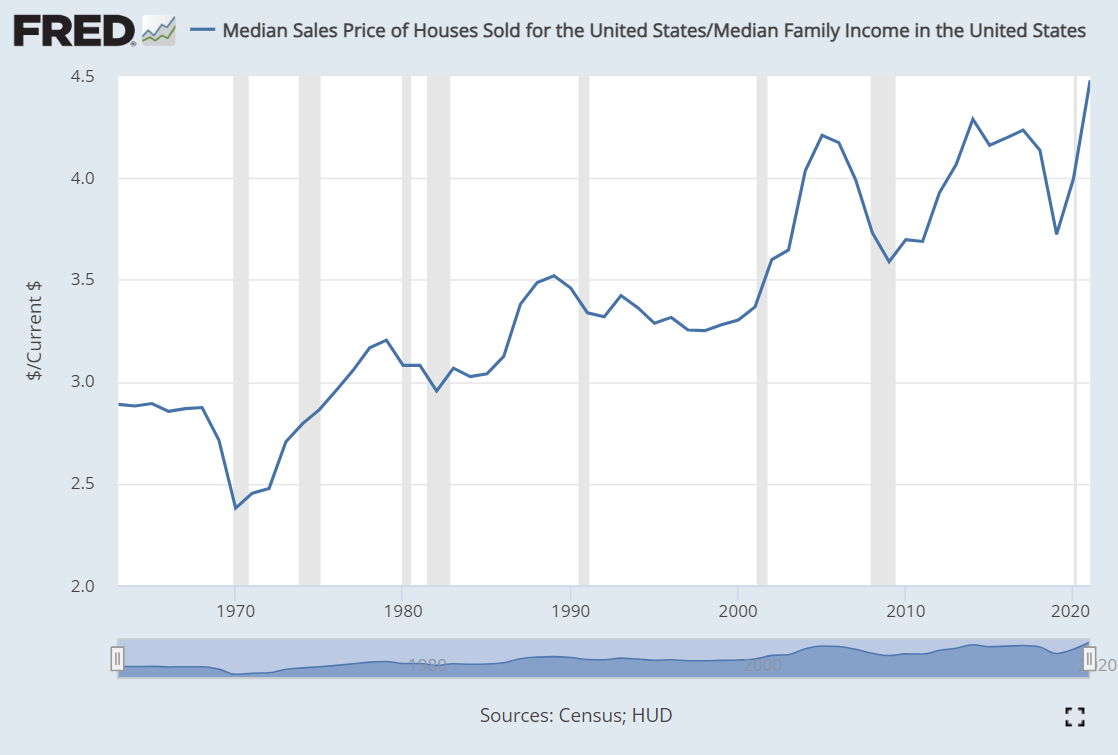

In 2021, the median U.S. household would have required roughly 4.5 years of income to buy the average house outright.

At first glance, this seems like terrific news for those waiting on a market crash. Asset prices often display a “gravitational force” toward a central figure, and the price-to-income ratio suggests that home values could fall from 20% to 40% to reach historic levels.

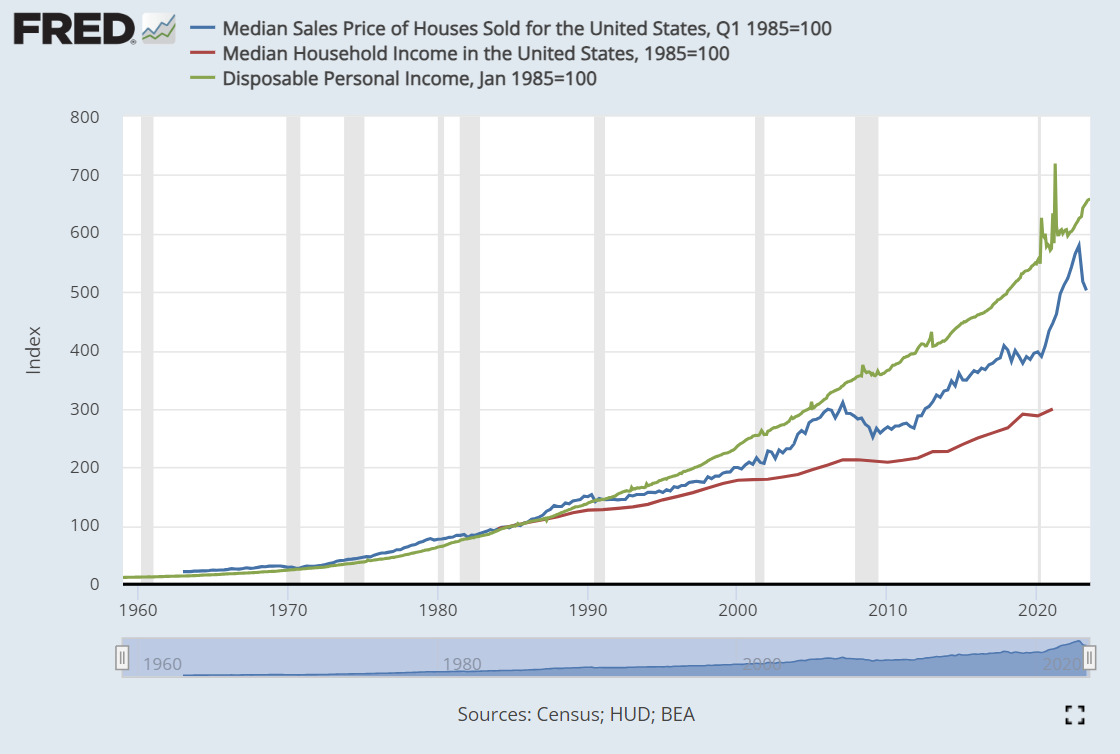

However, this single-price metric masks a broader shift in the cost of American goods. Since the mid-1980s, prices of electronics, apparel, and other imported goods have plummeted, allowing people to spend more on larger homes. For instance, the average 20-inch color TV cost $500 in 1985. Today, a modern 20-inch monitor, adjusted for inflation, sells for 95% less. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Americans today spend a quarter less on apparel than in 2006, even before adjusting for inflation.

These differences add up. According to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, disposable personal income has risen 30% since 1985, despite rising housing costs.

Much of this reflects the realities of global trade. Increased imports from low-cost labor countries have helped U.S. firms reduce the prices of easily imported goods, giving Americans a greater ability to spend on other things. Technological change has also played a role; manufacturing electronics today costs a fraction of what it did three decades ago.

Most importantly, America has gotten richer. That means prices in labor-intensive industries like housing, healthcare and educational services have risen relative to capital-intensive ones. A factory might be able to produce iPhones ten times faster than it did a decade ago, but a roofer can’t do their job any quicker than before. All else equal, that means the price of a roofer should rise more quickly relative to the cost of iPhones, even as the overall consumer gets better off.

Building Confidence

The number of new houses in America has also failed to meet demand. According to the most recent estimates from Freddie Mac, the country is short roughly 3.8 million housing units.

A similar shortage in the Canadian and Australian markets left markets unaffordable. The average home in Toronto now costs $1.16 million, or ten times household income. Meanwhile, land-constrained markets like Hong Kong, London and Singapore have seen high housing prices since at least the 1970s. When too many buyers chase too few houses, an unaffordability crisis generally follows.

American homebuilders have added to the shortfall, thanks to their memories from the 2008 financial crisis. The most recent data from DR Horton (NYSE:DHI), one of the country’s largest homebuilders, showed only a 6% increase in home sales in the most recent quarter.

“Our balanced capital approach focuses on being disciplined, flexible and opportunistic to support and to sustain an operating platform that produces consistent returns, growth and cash flow,” noted DR Horton CFO Bill Wheat. “We continue to maintain a strong balance sheet with low leverage and significant liquidity, which provides us with flexibility to adjust to changing market conditions.”

That means America’s new housing shortage should last until at least 2026, according to price estimates by Zillow. No homebuilder CEO has shown much willingness to take on leverage in the name of growth, and homebuyers are suffering the consequences.

Mortgaging One’s Future

Finally, many U.S. homes have remained off the market this year because of high mortgage rates. Most homeowners lack portable mortgages, so they get locked into their homes from owning fixed 30-year mortgages. Many economists term this the “golden handcuffs” effect.

That’s caused the number of existing home sales to plummet, keeping prices high. According to the National Association of Realtors, total existing home sales have dropped from 6.56 million in 2021 to 4.07 million in 2023. The numbers are even worse in the lower-end of the market. Sales of houses under $250,000 have fallen more than 20% in the past year alone.

The result has been a real estate market that has moved in an opposite direction to what rates might suggest. Since January, the median sales price of existing U.S. homes has risen 12.4% nationally, compared to a 9.1% increase in Canada and a 0% increase in the United Kingdom. Fixed 30-year mortgages — a very American phenomenon — mean that rate changes only affect homebuyer behavior on the way down, since people can refinance. When rates are high, consumers can afford to wait things out.

Where Will Home Prices Go From Here?

None of this will come as good news to American renters. Rental prices are already 20% higher than in 2019, and a return to office work suggests that city-center prices will keep going up.

Some local communities have begun tackling this issue, especially around affordable housing. In 2021, Massachusetts adopted a new zoning law that required cities and towns served by commuter rail to zone districts for multi-family housing. Washington State has made a similar push with “missing middle” housing to increase the availability of duplexes up to sixplexes.

But none of these measures will deflate housing costs anytime soon. The average new house requires between $150 to $200 per square foot to build, making them almost twice as expensive as existing homes. A shift toward apartment living will also take time, since these larger structures typically take multiple years from approval to completion.

Ironically, the Federal Reserve could hasten a price decline by cutting rates. The resulting decrease in mortgage rates will allow current homeowners to move and bring more units on the market. But with 10-year Treasuries still trading at decade-long highs, no one seems convinced that the Fed will do such a thing anytime soon. America’s home prices have no choice but to keep going up before they fall.

As of this writing, Tom Yeung did not hold (either directly or indirectly) any positions in the securities mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer, subject to the InvestorPlace.com Publishing Guidelines.